When I created The Journal of Boardgame Design, one of my goals was to pull the nature of board game writing up a notch, beyond game reviews that were intended to be buyer's recommendations and into the level of critical analysis. Treat games as an artform that could be analyzed in the same ways that music, painting, literature and film are treated. If this seems to raise game design to a level that isn't warranted, we should remember that there were times when dance and film were regarded as merely recreation and entertainment. As game design has become more ambitious, so should its criticism.

In the 1950's, Francois Truffaut advocated looking at film in a new way which became known as "Auteur Theory". According to Wikipedia:

In the 1950's, Francois Truffaut advocated looking at film in a new way which became known as "Auteur Theory". According to Wikipedia:"The auteur theory holds that a film, or an entire body of work, by a director (or, less commonly, a producer) reflects the personal vision and preoccupations of that director, as if she or he were the work's primary "author" (auteur).

"Truffaut's theory maintains that all good directors (and many bad ones) have such a distinctive style or consistent theme that their influence is unmistakable in the body of their work."

For a time, auteur theory was of interest only to academics and intellectuals, while ordinary filmgoers could care less about who the director of a film was. Your grandparents probably never talked about seeing the latest Billy Wilder movie (though they might have been aware of the latest Alfred Hitchcock movie.) Still, public awareness of the role of directors became widespread through movie critics who promoted the latest foreign film directors (including Truffaut), and in the 1980's the earth cracked open when names like Stephen Spielberg and Martin Scorcese became part of our daily vocabulary.

It seems as though we are coming in to a time when game designers are beginning to have the same visibility that film directors began to have thirty years ago. As in the 1970's, the talk is mostly among devotees, and mostly about Europeans. As once film had it's Truffaut, Bergman and Fassbinder, today boardgaming has its Teuber, Kramer and Knizia. Once there was a reawakened appreciation of Howard Hawks and today we rediscover the groundbreaking work of Sid Sackson.

It seems as though we are coming in to a time when game designers are beginning to have the same visibility that film directors began to have thirty years ago. As in the 1970's, the talk is mostly among devotees, and mostly about Europeans. As once film had it's Truffaut, Bergman and Fassbinder, today boardgaming has its Teuber, Kramer and Knizia. Once there was a reawakened appreciation of Howard Hawks and today we rediscover the groundbreaking work of Sid Sackson.Before we elevate game designers from being artisans to being auteurs we ought to ask: does this comparison really make sense? Is there really a basis in comparing games to films, music or literature? Can one really look at the body of work of a game designer and make out a distinctive style or consistent theme? To the extent that it is possible - is it of any consequence?

I didn't initially set out to write an article that questioned the value of examining the collected works of game designers. I set out to find a game designer whose body of work I could analyze, hoping to create a series around this. I soon hit a wall. It is difficult to identify a meaningfully consistent style in most designers. Even Reiner Knizia, who tended to create perfect efficient miniatures early in his career with games such as "Medici", "Modern Art", and "Tutankamen", soon moved on to create sprawling (by Eurogame standards) games such as "Euphrates & Tigris" and "Stephensons Rocket", which seem to have sprung out of an entirely different mind.

Then there is the question of what merit there is in the exercise. Take Rudiger Dorn. We could look at his three best games and indeed see a pattern. In "Traders of Genoa", "Goa", and "Louis XIV", Dorn uses a common mechanism to limit the choices that a player has. In each case, choices are laid out on an orthogonal board and players place markers on locations along a path (Call it the "poop dropping" mechanism). It's a nifty way to structure player choices, and best of all, it's a pattern! We've successfully applied auteur theory to game design!

Then there is the question of what merit there is in the exercise. Take Rudiger Dorn. We could look at his three best games and indeed see a pattern. In "Traders of Genoa", "Goa", and "Louis XIV", Dorn uses a common mechanism to limit the choices that a player has. In each case, choices are laid out on an orthogonal board and players place markers on locations along a path (Call it the "poop dropping" mechanism). It's a nifty way to structure player choices, and best of all, it's a pattern! We've successfully applied auteur theory to game design!Okay, so let's compare that observation with one that film critic Peter Rainer makes about director Brian De Palma in a recent Los Angeles Times essay.

"Despite the super-sophistication of his technique, in essence De Palma's movies express, at least for men in the audience, how sex was experienced as an adolescent. ... They capture the rage and mortification, the guilt, the tingle of voyeurism.

"One of the most unnerving things about De Palma's films, even more than their eruptive, gargoyle terror, is the suggestion that these adolescent anxieties are naggingly ever-present. The tyranny of sexual desire, woman as the Other — for most men, these fears still fly."

In contrast with Rainer's observations about Brian De Palma as an auteur, our own observations about Rudiger Dorn seem pretty lame.

The comparison, you might say, is unfair. A movie has a story; it has characters. It is meant to express something - whether it is the wonders of childhood, the anxieties of adolescence, or the alienation of adulthood. A game can't be expected to do all that or any of that. After all, it's just... a game. It's just a bunch of mechanisms.

Perhaps a game designer may not be able to express anything of consequence through his mechanisms, but what about his choice of theme?

The importance of theme no doubt varies across designers. Generally, being a game designer is a poor choice of occupation if theme is your intended means of expression.

Martin Wallace has chosen to maintain a high level of control in his games. He publishes mostly through companies such as Winsome and Warfrog, which he has close relations with, and which have either published his games directly or through licenses with companies that do not change his games. His game mechanisms tend to be closely related to the themes in his games. In a game such as Struggle of Empires, Wallace has chosen to express his thoughts on the drivers behind imperialism, and these thoughts are very clear in the game play.

Martin Wallace has chosen to maintain a high level of control in his games. He publishes mostly through companies such as Winsome and Warfrog, which he has close relations with, and which have either published his games directly or through licenses with companies that do not change his games. His game mechanisms tend to be closely related to the themes in his games. In a game such as Struggle of Empires, Wallace has chosen to express his thoughts on the drivers behind imperialism, and these thoughts are very clear in the game play. Most designers, however, find their themes to be controlled at the whim of publishers. Alan Moon and Richard Borg created a game which aimed to capture the spirit of combat in feudal Japan. By the time it was presented by Goldsieber as Wongar, the game was changed by its publisher to be about aboriginal Australian rituals!

Most designers, however, find their themes to be controlled at the whim of publishers. Alan Moon and Richard Borg created a game which aimed to capture the spirit of combat in feudal Japan. By the time it was presented by Goldsieber as Wongar, the game was changed by its publisher to be about aboriginal Australian rituals!In an interview in The Game Table, Reiner Knizia spoke of the relative lack of importance that theme has for for German publishers.

"In America, the theme is seen as the game where as in the European the game mechanics and the game system are seen as the game." Knizia tells a story about when he took a game prototype to America. It had an Egyptian theme and when an American publisher saw the theme they said, "We are not interested in this game, we have a game about Egypt and we don't need another." ... A few weeks later he ... showed the same game to a German publisher. "Oh, we are just in preparation of an Egyptian-themed game, so the Egyptian theme wouldn't work for us. But let's see the game first and then we can see what we'll do about the theme."

Imagine Mark Twain's editor reviewing "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" and telling him: "We loved the book and we'd like to publish it. We've kept the basic story about a trip down a river on a raft, only now we've set it in China, and it's about a spice trader who leaves his company to join a local man on a search for a ruby studded statue of Buddha that can make them both rich."

Imagine Mark Twain's editor reviewing "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" and telling him: "We loved the book and we'd like to publish it. We've kept the basic story about a trip down a river on a raft, only now we've set it in China, and it's about a spice trader who leaves his company to join a local man on a search for a ruby studded statue of Buddha that can make them both rich."Twain would probably have taken up another profession - something more honest and less prone to meddling, like accounting. Game designers carry on, unfazed.

So if a game's mechanisms don't express anything meaningful, and a game designer can't even control the theme of his game, what is left?

Reiner Knizia does believe that a game designer expresses his personal vision through his work. In his interview for The Game Table, he says:

"I think that every designer has his own handwriting. I am a scientist and that influences my character and how I see the world. So maybe my games have more of the analytical side stressed, not because I am doing this in awareness but more because that's who I am and that's how my world looks like. My approach is that the game should have very simple rules and depth of play comes out of these simple and unified rules. "

Knizia describes here not just a sort of mechanism, or a technique, but rather a guiding philosophy that indeed does reflect his personal vision. I emphasize the word "personal". Why should the rules be simple and unified? Do they make for a better game? Knizia offers no explanation, nor need he offer one. These principles are simply an expression of his personality.

A game with many rules designed to encourage players to explore the nooks and crannies in its mechanisms can be an excellent game - but it would not likely be a Knizia game. Reiner Knizia would of course never have invented a game like "Age of Renaissance", but I think that even "Power Grid" would have looked very different if designed by Knizia. Power Grid has relatively involved rules concerning the changes that occur every time the game enters a new "Phase"as the power plant market gets manipulated and supplies of commodities change. Specific rules create handicaps for leading players. Power Grid has been approached like a work of engineering in which a mechanism may be added to solve a specific problem. Knizia describes himself as a scientist - which along with his stated approach to game design implies that he believes function is more of a consequence of natural laws than an active attempt to manipulate them.

Game designers become auteurs when their style reflects not just a frequently used mechanism but rather an entire approach to gaming, and implies what they believe a game ought to be. In the case of Knizia the scientist, games manifest the complex possibilities that emerge from relatively simple natural laws. If Reiner Knizia - the game designer - is indeed a scientist, he is probably a physicist.

The games of Bruno Faidutti have sometimes been criticized for having too many chance and chaotic elements in them. I imagine his response would be: "guilty, proud of it." Faidutti seems to revel in unpredictibility, and wants his players to share in the fun. He pretty much declared his attitude to the world in one of his earliest published designs: "Knightmare Chess". That game starts with the great Western classic game, but gives players cards which allow them to muck around with the rules in unpredictible ways.

The games of Bruno Faidutti have sometimes been criticized for having too many chance and chaotic elements in them. I imagine his response would be: "guilty, proud of it." Faidutti seems to revel in unpredictibility, and wants his players to share in the fun. He pretty much declared his attitude to the world in one of his earliest published designs: "Knightmare Chess". That game starts with the great Western classic game, but gives players cards which allow them to muck around with the rules in unpredictible ways.To add unpredictibility to chess is a little like painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa. It takes a certain kind of person to do that. More than anything, it tells you a little about what his idea of "fun" is.

In "Citadels", Faidutti's most successful and celebrated game, players target each other with their special powers but in a highly unpredictible way. For example, a player who has taken the role of the "thief" can choose a character whom he plans to rob - but can only make a hunch as to which player he is actually robbing because players choose their characters secretly. This can lead to a lot of grumbling both from the thief, who may have targeted a player who has nothing to steal, and especially from a player who was trailing and became the unintended target (and especially when I'm that player!).

In "Citadels", Faidutti's most successful and celebrated game, players target each other with their special powers but in a highly unpredictible way. For example, a player who has taken the role of the "thief" can choose a character whom he plans to rob - but can only make a hunch as to which player he is actually robbing because players choose their characters secretly. This can lead to a lot of grumbling both from the thief, who may have targeted a player who has nothing to steal, and especially from a player who was trailing and became the unintended target (and especially when I'm that player!).Faidutti's games are often described as being "chaotic" and it's rarely intended as a compliment. The pattern in his games are however so unmistakable that it is clear that Bruno Faidutti revels in the chaos, builds it into the games intentionally, and regards unpredictibility as an essential part of the fun in gaming. I think that the only way to properly appreciate many of his games is to play them in the spirit intended - partly as a battle of wits, but equally as a wild ride. Climb onto the bull and hold on!

This attitude toward finding the fun in a game can manifest itself even into the simplest things - like whether a card game should have a player draw his card before or after his turn. On his website, Faidutti describes the difference:

"The 'draw a card, then play a card' rule ... strengthens the surprise and fun aspect of the game, to the detriment of deep thought and strategy. During opponents’ turns, one will try to think of what one will do next, but will also day-dream of the card one could draw when one’s turn comes. This card, when drawn, may cause some impulsive reaction, and may be sometimes a bad move – but that’s an important part of the game fun. The 'play a card, then draw a card' rule emphasizes on strategic planning. It means one can think of all the possible moves, and check their possible effects, before one’s turn comes. "

From everything we've seen about Bruno Faidutti so far, his preference should be no surprise:

"(Play a card, draw a card) sure makes the game deeper and more challenging, but it also makes it feel less fun and less natural."

Reiner Knizia and Bruno Faidutti are two of the most stylistically assertive auteurs in the game world. You may or may not like their games, but the reasoning behind your opinion is likely to be closely related to the difference between what you find to be fun and what each designer believes to be so. This strong design philosophy is what separates game auteurs from journeymen whose designs lack personal style.

It is really a strong design philosophy and not particular mechanics that define the auteur. When evaluating a designer, the interesting question is: "What effect does he want to achieve?" and not "What technique does he tend to rely on?"

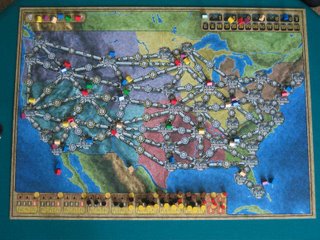

Compare Alan Moon and the team of Wolfgang Kramer and Michael Kiesling. In many of Alan Moon's games, players draw cards from a face-up selection (Elfenland, Union Pacific, Ticket to Ride). Often players are given from one to three actions in a turn (draw cards or use cards in both Union Pacific and Ticket to Ride, the limited actions in Reibach/Get the Goods or Andromeda). On the other hand, Kramer & Kiesling have frequently used action point mechanisms where players get from 6-10 AP in a turn with myriad possibilities on how to spend them (Torres, Tikal, Java, Mexica, Bison). The obvious reason that each designer tends to reuse his mechanisms is that the mechanism works, is reliable, and is flexible enough to solve certain design problems in many games.

Compare Alan Moon and the team of Wolfgang Kramer and Michael Kiesling. In many of Alan Moon's games, players draw cards from a face-up selection (Elfenland, Union Pacific, Ticket to Ride). Often players are given from one to three actions in a turn (draw cards or use cards in both Union Pacific and Ticket to Ride, the limited actions in Reibach/Get the Goods or Andromeda). On the other hand, Kramer & Kiesling have frequently used action point mechanisms where players get from 6-10 AP in a turn with myriad possibilities on how to spend them (Torres, Tikal, Java, Mexica, Bison). The obvious reason that each designer tends to reuse his mechanisms is that the mechanism works, is reliable, and is flexible enough to solve certain design problems in many games.Apart from that, each technique reflects a different philosophy. By presenting users with three or four card choices, Alan Moon is pushing some unpredictibility into the lap of his players and forcing them to choose between some very limited options. The chance and unpredictibility of the choices forces the user to adapt to the unexpected, and those key basic alternatives ("play a card or draw a card?" are the essence of the "Agonizing Decision". In contrast, Kramer & Kiesling prefer to be far more open ended. Their gamers' games challenge a player by dumping a large quantity of resources into his lap, presenting him with decision trees that have an intricate network of branches, and demand that the player builds a strategy which uses these resources most effectively.

Alan Moon seems to see the greatest joy in gaming as confronting hard decisions. Kramer and Kiesling see the joy come from the challenge of managing resources and exploiting opportunities.

That pattern has more meaning if it can be applied to other games which don't use the same mechanisms as card drafts or action points. For example, in San Marco, Alan Moon gives players limited hard decisions - but with an entirely different mechanism. He gives one player a series of selected action cards and challenges him to divide them into stacks which his opponents may choose from. Then he gives the remaining players the very limited - but no less agonizing - responsibility to choose the one stack with the most useful actions and least painful penalties.

When Wolfgang Kramer created "Hacienda", he used a card drafting mechanism similar to that found in games such as "Union Pacific" and Ticket to Ride, but he puts these cards to a much more open ended use than is typically seen in Alan Moon's games. In Moon's "Union Pacific" the cards a player draws are fairly passive assets. You draw them, you play them in front of you, and hopefully you score with them. Even in "Ticket to Ride", players have very specific paths that they are trying to take, and they draw cards they need in order to complete those paths. The tension comes from deciding when to draw, when to play, and from dealing with the need to make detours. It is usually self evident where a particular set of cards needs to be placed for a player to achieve his goals. On the other hand, the cards in Hacienda are open ended resources which can often be placed in many different places. Having a set of any cards is just the beginning of the challenge to the player who needs to construct a plan on how to use them most effectively.

When Wolfgang Kramer created "Hacienda", he used a card drafting mechanism similar to that found in games such as "Union Pacific" and Ticket to Ride, but he puts these cards to a much more open ended use than is typically seen in Alan Moon's games. In Moon's "Union Pacific" the cards a player draws are fairly passive assets. You draw them, you play them in front of you, and hopefully you score with them. Even in "Ticket to Ride", players have very specific paths that they are trying to take, and they draw cards they need in order to complete those paths. The tension comes from deciding when to draw, when to play, and from dealing with the need to make detours. It is usually self evident where a particular set of cards needs to be placed for a player to achieve his goals. On the other hand, the cards in Hacienda are open ended resources which can often be placed in many different places. Having a set of any cards is just the beginning of the challenge to the player who needs to construct a plan on how to use them most effectively.Two designers take a similar mechanism - a multiple choice card draft - but treat the use of the cards in entirely different ways. Each use reflects what its respective designer regards to be the interesting challenge in a game.

How, then, are we to interpret games such as Kramer's "That's Life", a family game which offers players very limited choices? How does such a simple game fit in as a part of the designer's stylistic signature? I think that the most honest answer is: "it doesn't." Game designers, especially professionals, need to develop a large number of games every year to be economically viable. All of them will to some degree reflect the designer's values, but many will still be journeymen games that are principally created just to meet the needs of publishers and the public.

Another reason a designer may venture outside his style is just to experiment and mix it up a little. So from Reiner Knizia we'll see a game like "Blue Moon", which has lots of different cards

with different powers, and seems a little elaborate for a Knizia game (although its rules are, true to form, very simple.) It seemed very out-of-character when Bruno Faidutti worked on the redevelopment of "Warrior Knights", a long and relatively complex war game, but there it is. Of course, sometimes experimentation is also a way of moving on to something new permanently. We may never again see Reiner Knizia offer up more minimalist masterpieces in the mold of "Modern Art" and "Medici" again (I swear - that run of "M's" was NOT intentional!).

with different powers, and seems a little elaborate for a Knizia game (although its rules are, true to form, very simple.) It seemed very out-of-character when Bruno Faidutti worked on the redevelopment of "Warrior Knights", a long and relatively complex war game, but there it is. Of course, sometimes experimentation is also a way of moving on to something new permanently. We may never again see Reiner Knizia offer up more minimalist masterpieces in the mold of "Modern Art" and "Medici" again (I swear - that run of "M's" was NOT intentional!).Finally, sometimes an auteur's fingerprints may be a little hidden. The task of decoding and understanding the art of game designers is in its infancy, and in time, as the hobby grows and more people become fascinated with this issue, new minds will discover patterns that are overlooked today. "Stephensons' Rocket" is often regarded as uncharacteristically involved for a Reiner Knizia game. Yet it has only four pages of rules and takes about thirty paragraphs to explain. Compare that with Kramer and Kiesling's "Mexica", which was described as "family friendly" when it came out, and yet has ten pages of rules and about ninety paragraphs. Knizia really does stick to his word when he talks of creating games with "simple and unified rules" even when he slips to the complex side of the spectrum. Switching to film again, there may have been a time when it seemed only coincidental that movies such as "Sunset Boulevard", "Some Like It Hot" and "The Apartment" sprung from the same mind, that of Billy Wilder, but in time admirers have come to see the sexual cynicism that unites them all.

Indeed there is a Catch-22 that impedes our ability to comfortably see the auteur behind the game designer. In order for a designer to really establish his stylistic handwriting, he needs to design and publish many games. But any designer who does so must increasingly design some of his games for purely economic reasons, to satisfy the tastes of a large public audience. Those tastes may or may not coincide with what especially interests the designer.

Some of the most highly rated games to have been published in recent years are not from the great well-established auteurs we've mentioned above, but instead are games from new designers with little or no track record which we can examine for trends. What will the fifth, sixth or tenth game by William Attia, designer of Caylus, be like? Future games will hold new secrets to unlock. Some designers will develop strong styles in their games, while others may produce excellent games but without developing a strong personal style. For many of us players, the joy comes not only from the playing but also from the appreciation of the person behind the game.

Some of the most highly rated games to have been published in recent years are not from the great well-established auteurs we've mentioned above, but instead are games from new designers with little or no track record which we can examine for trends. What will the fifth, sixth or tenth game by William Attia, designer of Caylus, be like? Future games will hold new secrets to unlock. Some designers will develop strong styles in their games, while others may produce excellent games but without developing a strong personal style. For many of us players, the joy comes not only from the playing but also from the appreciation of the person behind the game.